.jpg)

.jpg)

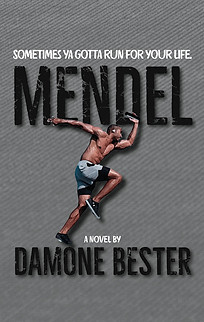

An excerpt from Mendel

Love is sacrificial and often comes at great cost. My parents taught me that through their own sacrifices. It took me a while to learn it, but once I did, it was a lesson I have never forgotten. One doesn’t simply live in my hood; you survive.

Yet not everyone can survive growing up the Chicago way. It takes a certain kind of toughness, tenacity, grit. Some people fold, others break; few survive. Survival looks different to many people. For a young Black male living on the South Side of Chicago, survival isn’t guaranteed. That’s why my story’s atypical, and maybe by sharing my story I can help other kids my age too.

My life in Chicago was—I loved Chicago. I still do. The neighborhoods, the parties, the music, my family, friends, enemies, even the gangs, all had a part in raising me. Everything about Chicago—especially my old high school, Mendel—shaped me into the person I am today.

Founded back in the fall of 1951, Mendel was run by the Augustinians. It was named after Gregor Mendel, who was called the Father of Genetics. My old high school sat on a luxurious plot of land nearing forty acres.

During the spring and summertime, Mendel looked like it had been plopped down in the middle of a plush forest. Green was everywhere. Huge shrubs and sky-scraping evergreens stretched for blocks, encircling the monstrous campus.

Bordering the prickly pines was a continuous chain-linked fence topped with barbwire that surrounded the entire school. The never-ending fence was about eight feet tall and was so close to the trees that the brush needles protruded out the mesh gate. This made Mendel look more like an impenetrable fortress than an inner- city high school.

People constantly joked that I attended high school on a college campus. Mendel even had a pond smack dab in front of the school’s main building. It was rumored the pond was originally made to look like the capital letter P for Pullman. That was the name of the school before it was Mendel, Pullman Tech. I believed the rumors were true because there was an old, corroded patch of land at the north end of the pond. It was clear to me that this “island” probably served as the hollowed-out portion of the capital letter P. Over the years, the apparently once beautiful pond morphed into the shimmering gray puddle that we were stuck with.

During my tenure at Mendel, many freshmen got dumped into the school’s pond. It was almost like a rite of passage for seniors to dunk the freshman. Thankfully, I never had the privilege of being dunked. Neither did I attempt to drown any freshman. Although, there were a couple that I wanted to humiliate in the waters of “Lake Mendel,” like when Prince embarrassed Apollonia in Purple Rain. But I didn’t want to get suspended.

On either side of the main building, where most of the classes were held, were two other buildings. The tan brick building to the left was Mendel’s gymnasium and cafeteria. That’s where all the good grub, exciting hoop squad games, and after parties went down.

The one on the right was the school’s monastery. That’s where the chemistry lab, the art classes, and the band practices were held. Not to mention where we would congregate for Mass every week like clockwork. Mendel was a Catholic college preparatory school situated in the Roseland community on the city’s South Side. Unfortunately, my neighborhood gained the notoriety of being called the Wild-Wild or as others called it The Wild Hundreds. Not the kind of monikers you want your community to be known for, being wild.

Yet on Mendel’s campus, my crew and I always felt safe. We were a city unto ourselves, the students, faculty, and staff. Within Mendel’s “city” gates, both the teachers and students strived for excellence. That was their reputation way before I got there. In fact, many of the teachers at Mendel were once students. That showed how special of a place Mendel really was to have former students come back there to teach. The Mendel community had always been a close-knit family.

And in every family, there’s a history that laid the foundation for the future.

One of the things I loved about Mendel was they didn’t have the same old classes that every other school had: English 101, Intermediate Algebra, Geography. Boring! We had classes like Life Skills, the private school’s version of Home Economics. Life Skills was taught by Brother Tyler. In that class, we learned how to balance a checkbook, create a budget, shop for groceries, even change a tire.

In Mrs. Epps class, My Own Biz, for juniors and seniors, we learned how to set up a business plan, learned whether to become a sole proprietor or an LLC, learned

how to invest in real estate, and learned how to gauge if a business would turn a profit or fold in the first two years.

But my all-time favorite class was Morality & Ethics, taught, oddly enough by Mrs. Morales. Mrs. Morales was a gorgeous, fiery Latina. My boys and I loved Morality & Ethics class because we could argue at the top of our lungs when debating our point.

The way Mrs. Morales’ class worked was she would introduce a topic at the beginning of class. Then we had ten minutes to come up with our arguments as to why the topic was or was not morally ethical and we’d discuss the topic for the majority of the class. During the last five to ten minutes, Mrs. Morales would give her supposition of the topic. It was great. Sometimes she would break us up into teams, other times, she’d have us fend for ourselves, individually.

But it was midterms; that meant we had to write out our answers in essay form. I had already zipped through my exam and was daydreaming about how horrible Christmas break was going to be when the school bell rudely interrupted.

I whipped my head around. A parade of classmates passed my desk donning their mandatory private-school dress code attire. The girls in their white, pink, or pastel blue blouses with black or gray skirts. Guys with our gray, black, or navy-blue slacks and cardigans along with white or pastel button-down shirts. We were already looked at a bit differently by our public-school friends for going to private school so, most of us felt that we were branded by having to wear uniforms on top of it.

Since Mendel’s inception, we had been an all-boy’s school. Yet due to increasing financial woes, we turned co-ed that semester to expand admissions, which made for a pleasant experience.

The hallways suddenly smelled fresh and perfumy. Guys didn’t beef as much anymore because they wanted to show how popular and cool they were. The girls at Mendel were attracted to a smidgen of bad boy. No one really wanted an outright hoodlum. And for some reason, even most of the teachers seemed nicer once the girls arrived.

We descended upon Mrs. Morales’ desk like a gaggle of geese being fed Ritz crackers. I was last in line to hand in my exam. I placed my test on the desk and turned to leave. Mrs. Morales’ accented shriek stopped me dead in my tracks. I looked back over my shoulder.

Mrs. Morales waved me over.

I huffed out a sigh and obeyed her command. Her eyes peered at me over the top of her wire rimmed glasses as I approached. She waited patiently for the last student to exit.

“Thought about what we discussed?”

“Some,” I answered respectfully unenthused.

“Well?”

“I. . .I don’t know.”

Mrs. Morales sighed a deep sigh and leaned back in her chair, “See the nine o’clock news last night?”

“No.”

“There was a student, graduated from Julian last year,” she sat up again. “He wasn’t working. Didn’t go to college. Just hanging around taking the year to decide what he wanted to do with his life, family says. He was shot in the head yesterday, died on the spot. You know why?”

“Any number of reasons. Owed somebody money, disrespected someone, um—”

“No. He didn’t have a plan. You only have one semester left, BJ. What’s your plan?”

“I don’t know Mrs. Morales.”

“Armed forces?”

“No.”

“College?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Who has the money for that?”

“Get a scholarship.”

“A scholarship? Doing what?”

“I don’t care. Anything Brandon.”

Mrs. Morales took a deep breath turning her head slightly. She removed her glasses. Looking up at me genuinely, calmly, she said, “You need to come up with a plan for your life, BJ, or you’ll be the next person shot ‘for any number of reasons.’ Comprende?”

I nodded.

“Now, go on. You don’t want to be late picking up Monica.”

Even though she dismissed me, I knew she wasn’t finished with this discussion by a long shot.

“Have a good Christmas,” I said softly.

“Mm-Hmm, you too,” Mrs. Morales replied scooping up the test papers. I could tell by the way she banged the exams on the desk straightening them into a pile she was slightly annoyed with me. I wish I cared more than I did. Truth was, I didn’t know what the future held for me. I didn’t care whether I lived or died.